- Home

- James Trettwer

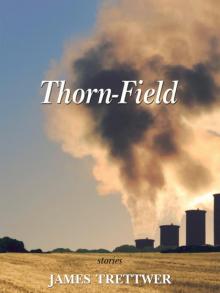

Thorn-Field

Thorn-Field Read online

©James Trettwer, 2018

All rights reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

Thistledown Press Ltd.

410 2nd Avenue North

Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, S7K 2C3

www.thistledownpress.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Trettwer, James, author

Thorn-field / James Trettwer.

Short stories.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77187-170-9 (softcover).—ISBN 978-1-77187-171-6 (HTML).—ISBN 978-1-77187-172-3 (PDF)

I. Title.

PS8639.R4785T56 2018 C813'.6 C2018-904559-0

C2018-904560-4

Cover and book design by Jackie Forrie

Printed and bound in Canada

An earlier version of “Godsend” was originally published in TRANSITION magazine. “Leaving With Lena” was previously published in Wanderlust: Stories on the Move, by Thistledown Press. The poem “Heavy Water” is a portion of “The Depths” previously published in Arborealis: A Canadian Anthology of Poetry, by The Ontario Poetry Society.

Thistledown Press gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts, the Saskatchewan Arts Board, and the Government of Canada for its publishing program.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

“Bring It On” was a winner in the SWG Short Manuscript Awards for fiction. The Thorn-Field collection was a winner in the SWG John V. Hick’s Long Manuscript Award. Thank you to the Guild for these opportunities.

Many hugs to Byrna Barclay — mentor and motivator by boot — without you, this collection would never have been. Supportive feedback on early versions of the stories by present and past members of the Bees writers group is much appreciated. To gillian harding-russell and Connie Gault, your generous feedback and support is also much appreciated. Linda Biasotto, you were with me in English 252 and during all these intervening years, your ongoing support is incalculable. Duff Marshall, many thanks for that initial encouragement all those years ago — ou kept me going. Michael Kenyon, couldn’t have done it without you. Thank you to Thistledown Press for taking all this on.

To my family, Coree and Krista, the first to hear these stories, your early feedback was invaluable. Sherry, I wouldn’t have been able to pull any of this off if you weren’t there for me. I am most grateful to you all.

Author’s Note: A valuable source in the writing of some of the stories in this book is John Burton’s Potash: An Inside Account of Saskatchewan’s Pink Gold, Regina: University of Regina Press, 2014. For the sake of storytelling, I have taken liberties with some historical facts. At the time of writing, there are no crown owned or operated potash mines in Saskatchewan. There are also inaccuracies in potash mining operations in this collection because I have taken narrative license with some details for the sake of story. Any errors or omissions are entirely on me.

for Byrna

CONTENTS

Threading Through Thorn-Fields

Lew LeBelle Loogin in the Land of the Looginaires

Leaving With Lena

Godsend

Bring It On

Blue

Iliana’s Daily Reminders

The Catherine Sessions

This Girl Next Door

Threading Through Thorn-Fields

LOURDES FLOATS. SHE DRIFTS OVER the Liverwood Potash Corporation mine. The mine’s plume is bright-white, reflecting a waning gibbous moon in a starless sky. Drifting with the plume on its lazy, southeasterly course, she veers toward the town of Liverwood. Descending, she passes over Liverwood Creek. She knows what is about to happen.

She tries to steer toward a treed hollow nestled in an oxbow of the creek near the Motel 6. She catches a glimpse of moon reflecting on water. Birch and Laurel Leaf Willow enclose the hollow. The creek’s shore is thick with Canadian thistle. The creekbed is exposed and dry while the hollow morphs into a flat, endless plain of thistles, the thick stocks six feet high, their purple flowers open and turned toward the plume — their surrogate sunshine. The lush growth suddenly shrivels and turns tinder brown as if poisoned by a toxic rain.

Through the middle of that brown field, Lourdes runs. The thorns on the shrivelled and spiky leaves and stalks shred her pajamas and ravage her exposed flesh and bare feet. She doesn’t feel any pain. Only a tingling on her hot, sweating skin.

The thorny stalks writhe. They entwine her legs and she falls on her face. She is naked from the waist down, prone on her stomach, and also watching from the ether. In the surrounding light — neither dark nor sunlit but brown as the dead field — a thistle’s lone flower, purple and vibrant, lifts from the thorns, then it too fades to brown and shrivels into a hard, spear-shaped seedpod. Thorns seize Lourdes’ ankles, biting to the bone, and force her legs apart. The seedpod thrusts between her inner thighs. Thrusts inside her.

A newborn baby cries once. She feels her womb explode.

Lourdes opens her eyes. Drenched in sweat, she thinks of Mary Bliss — then her father. She retreats to the hollow in the oxbow of the creek not far from the motel. Her hollow.

She sits high in a birch tree near the shore.

Looking down, Lourdes sees her eleven-year-old self enter the hollow.

Her father died in a mine accident two weeks ago. She is staying with the Treadwells who own the Motel 6 while her mother, Edna, is off — somewhere. The Treadwells let her stay by herself in the hollow as long as she promises that she will stay away from the creek.

A crow perches on a lower branch of the birch. It’s head cocked, the bird stares at its dead mate lying on the ground. Lourdes leans against the lone picnic table and studies both birds. It is her birch-hollow pair and it is the male that is still alive; he has the iridescent purple sheen across his plumage. Lourdes approaches the dead bird. She picks it up, cupping it in both palms. The female crow has been shot through her upper shoulder.

The male croaks a single, throaty caw. He does not fly away when Lourdes carries his mate to the creek’s shore. He lets out another plaintive croak, hops to the other side of branch and watches, head again cocked to one side.

With her bare hands, Lourdes digs a hole in the muck. She buries the female beside a single thick-stemmed Canadian thistle. The thistle, with its many purple flowers drooping in this dappled morning light, will be the grave marker.

For the next few days, any time Lourdes goes to the hollow, the male flies up from the grave to the birch and perches on that same branch. He watches her until she leaves. She does not know what the male does when she is not in the hollow.

Lourdes sits at the picnic table and leafs through the Scholastic book, Anne Frank — Beyond the Diary. Mr. Treadwell gave her the book to read and said she should think about Anne, “who was young just like you.” She doesn’t understand what Mr. Treadwell wants her to think and she can’t relate to the story. But she does wonder how so many families could get along all crammed into an attic together.

The male croaks his single, throaty caw. This gets her attention. The bird flies down and lands on the very spot beside the thistle where his mate is buried. He lets out a crow’s typical and raucous caw-caw-caw and zooms up, buzzing her. A wingtip brushes her hair and he is gone. See, she tells herself, holding the book against her chest, I’m not the only one suffering.

Damp with sweat from another dream of the

Thorn-Field, Lourdes is calm. She is so calm, she is not bothered by the fact that her sixteenth birthday was forgotten the previous Saturday. She did not expect a party anyway, or even acknowledgement of the occasion.

After stretching, she rolls on her side. Her rickety twin bed creaks. She stares at the faded beige walls of her bedroom. It is the smaller of two bedrooms of a mobile home where she lives with Edna and whatever boyfriend her mother might have staying with her.

The carpets in the place are worn down to the underside mesh in heavy traffic areas. The kitchen and bathroom linoleum is worse, with the bare wood of the trailer’s floor exposed. The windows leak and water has stained the frames brown. Black, flaky mould blooms from the corners of the outside walls. The front door has a lock but a hard push will open it. Snow piles inside the door in winter and the furnace roars constantly. All taps drip and the toilet flushes itself every half hour.

Then there are the other noises — Edna, yelling, moaning, screaming, the blare of the portable television her mother constantly watches: snowy afternoon soap operas and dramas on the two available non-cable stations. The TV occasionally disappears to the pawnshop near month’s end, when money is short. Some months, the TV is returned by Herb, the owner of Liverwood Pawn and Surplus. Herb then stays the next few nights with Edna. He is the current boyfriend and Lourdes can hear him snoring in her mother’s bedroom right now.

The noises from Edna’s bedroom are always intolerable. They are harsh, with severe thumping, sometimes slapping sounds, and swearing. Herb, especially, likes to talk. Lourdes can only cover her head with her pillow and turn up the MP3 player her father gave her before he died.

But the worst sound of all is silence. When the furnace isn’t running, when Edna isn’t moaning, or rambling in some kind of drug- or alcohol-induced stupor — at least letting Lourdes know she is still alive — the silence smothers her. Suffocates her. On these occasions she snaps awake. She lies in bed, panic building, thinking she can escape if Edna would only die of an overdose. Guilt immediately knots her stomach. Then, no matter how hard she tries, she can’t go back to sleep until she checks to see if Edna is alive. She has to get up to check on her mother. Then she can’t sleep afterward anyway with Edna’s raspy breathing, which may cease at any time, echoing in her ears. Lourdes wants out but not at the expense of another person’s life. At the same time she doesn’t know how she can stay much longer.

She rolls on her back and stretches again. Her skin feels crusty now that the sweat has dried. She hears Herb still snoring and decides to shower.

Letting a cool flow wash away the crust first, she turns the water off to lather her thick, wavy, copper-red locks that hang down past her shoulder blades. Then she lathers her lightly freckled body.

The bathroom door slams open. Like the front door, the bathroom lock works only occasionally. Herb pulls the shower curtain back. His shirt is off, exposing thick black chest hair. He is scrawny, with ribs showing under his droopy man-boobs. He has a potbelly from too much beer and sitting behind his pawnshop counter or lounging on Edna’s bed or couch.

He sees Lourdes and gawks, open-mouthed. She instinctively covers her breasts with one arm and reaches the other down, covering her genitals.

Herb, still gawking, scratches his mass of thick black hair, combed straight up, on his oversized head. Then he scratches one of his long sideburns. The other hand kneads his checked, lumberjack shirt. He scans her body up and down.

Lourdes stares hard at him. She feels her face burn. Her stomach burn. The burn turns into a hateful rage that bursts up and out. She does not scream or yell but speaks in a low voice through clenched teeth. “What the fuck are you doing?”

“I, I didn’t hear the water running.” Herb’s voice is half an octave higher than its normal rat-like squeak. He shifts his body, cocks his head and grins. “They say you should save water and shower with a friend, you know. And now that you’re sixteen, Edna says, it’d be all legal. And just so’s you know, I like ’em chunky.”

This time Lourdes does scream. “Get the fuck out of here before I gut you like the fucking pig you are.” She takes one step out of the tub, fists raised.

Herb steps back. His eyes bulge like those of a terrified mouse caught in a live trap. From somewhere, Edna calls, “Herb?” Face returning to its normal shifty sneer, he lifts his chin and says, “Maybe next time, punkin. I hear a real woman calling.” Shoulders hunched, he shuffles out of the bathroom.

She stumbles back into the tub and flings the shower curtain closed. She turns the water to hot. Shaking, she slides down and sits in the tub. Squeezing her stomach flab in both hands until it hurts, she is afraid the skeleton image of Herb is now permanently etched in her mind. The shakes turn to a quiver while the water continues to flow over her.

She does not cry.

The next morning, a sunshiny Sunday, Lourdes is at the stove. It has only three working burners and the white enamel is chipped and blackened all across the stove top. No matter how hard she tries, she can’t get the stove clean. She also cannot repair the broken hinge on the oven door. She doesn’t have the tools or a replacement hinge, both of which Edna refuses to buy. So the door hangs askew and the oven never bakes properly.

Eggs and rye bread, the day-old bread she always buys on her way home from school, fry in their battered skillet. The skillet’s plastic handle has been long broken. She has jury-rigged a replacement handle with a cut-down, wooden mop pole fastened with a nut and bolt. When the skillet handle first broke, Edna tried to fry with a pot.

Edna manages to shuffle into the kitchen just when Lourdes moves the bread and eggs onto plates. She pauses and leans against the wall for support. She takes a breath and staggers toward the kitchen table. Falling forward, she grabs the back of the chrome chair with both hands and plops down with a sigh. Her whole body sags.

Edna is becoming more and more gaunt. At five foot four, she weighs barely 100 pounds. Her thighs are blackened with finger-shaped bruises. Her knees and shins are covered in red scrapes and scabs. Her stringy hair is falling out. Lourdes finds strands everywhere, including inside the bread bag after Edna has grabbed a slice and eaten it right over the bag without closing it. Her pockmarked cheeks and dowager’s hump make her look like a woman in her seventies even though she is only thirty-six years old.

This morning, she wears a long-sleeved, beige turtleneck sweater that hangs down to her upper thighs. It is a hot June day so the sweater is likely meant to hide traces of whatever new experiments are tracking down her arms. Her button nose is always raw and red, with dried skin hanging on the edges of her nostrils. Her long delicate fingers, that once played their electric piano before it was pawned at Herb’s, are yellow with nicotine and already gnarled with arthritis.

Lourdes bangs Edna’s plate in front of her, then sits across the table, also banging her own plate in place. Edna ignores her except for a quick glance in her direction. She is fully aware of the smouldering rage in her daughter. Careful not to glance up again, she begins to eat with her fingers, sopping egg with the bread, face hanging over her plate.

Lourdes says, “I don’t want that drug-pushing Herb here anymore. Same with your other creepy lovers. Do it at their place. They make me sick.”

“You shouldn’t provoke Herb like that,” Edna says, face still over her plate.

“He barged in on me. The door was supposed to be locked. You should get it fixed.”

“Locked.” Edna snorts. “How was he supposed to know you were in there? You didn’t have the water on.”

“I don’t waste water while I soap up. I keep telling you that.”

“And I keep telling you, water is included in the lot fees. Who cares how much you use?”

“That’s not the point.”

Edna finally looks up. “Yeah, the point is, you tried to entice him, you fat little slut. He told me so. You know he likes ’em fat.”

For the second time in less than twenty-four hours Lourdes is in shock. S

he can’t respond.

“Can’t think of a come back because it’s the truth.” Edna sneers. “I dare you to deny it. You wanted him in there so he could fuck you.”

“Fuck you!” Lourdes still can’t swallow. She jumps up, clenches her fists. Unclenches them. The thought of being with Herb makes her want to vomit. Bile burns her throat.

Edna staggers to her feet, using the table for support. “Deny it. You can’t. You want to take him away from me. It wasn’t bad enough you fucked Barton and then you lost the baby.”

She erupts. Throws her plate at Edna. She misses only because of a hasty throw. The plate shatters against a cupboard door. Food and lethal fragments fly. The cupboard door cracks.

She races around the table. Edna tries to slap her when she lunges. She grabs Edna’s wrist. Twists, hard. Something snaps when she bends Edna’s arm down and behind her and forces her to her knees.

Edna screams. “You’re hurting me. Stop. I didn’t mean it about Mary. I’m sorry.”

But the damage is done. Irrevocable. Lourdes pushes her mother to the floor, hard, with both hands. Edna quickly rolls over and scuttles under the kitchen table, whimpering, “Lourdes. Please. Stop.”

Just as in her dreams, when she hears the baby’s strangled cry in dead fields of shredding thorns, her arms become crow wings. She flaps hard and propels herself to the ceiling. Lightheaded from being airborne, she drifts along the ceiling and watches herself.

In the hospital — almost a year ago now — she was not allowed to even hold her baby to say goodbye.

She stomps to her bedroom and rips her cardboard suitcase from the closet. She dumps the old graded school papers worth keeping and the few books she owns onto the closet floor. She grabs her four pairs of panties, all riddled with holes and coming apart at the seams, her three bras, beaded from wear, and her two pairs of jeans and six over-sized T-shirts and flings them into the suitcase. Almost as an afterthought, she takes her only pair of pyjamas from under her pillow and drops them on top of the T-shirts. Pulling the jeans drawer out of her bureau, she lifts out her spiral notebook journals — hidden where Edna and her friends would probably never find them — and tucks them inside the lid pocket of the suitcase. She grabs her MP3 player and stomps to the bathroom. She packs shampoo, toothbrush and toothpaste, and seizes all of the tampons, including Edna’s supply.

Thorn-Field

Thorn-Field